Stack-based programming with a human face (part two)

As expected, the previous post has caused controversial comments. Someone comfortable with the existing Fort to address issues, someone (like me) annoyed by its features.

Let's just dot the i: I'm not trying to write a replacement for the Fort. Fort mid — level family of programming languages that continues productive to solve tasks and at peace not going. But I think in a different niche: high-level stack-based language with an emphasis on ease of reading programmes for beginners (if possible). A great tradition and vysokoprochnost has its advantages, but it lost some features (including positive) of the Fort.

The new imaginary language of their own philosophy and their concepts. This is what I will continue to write.

Every Creator of language, which is not only recursion, sooner or later think about a set of circular structures. I prefer first to consider the design of a common, universal cycle, from which we can derive the rest, and then on the basis of practical experience, add additional designs for the most common cases.

The main loop looks like this:

the

Scary, isn't it? But really it is only a formal description, works all elementary. Each iteration executed all words after repeat. Then calculation of the when conditions. If condition1 is true, execute слова1 and the cycle starts a new iteration from the beginning. If condition1 is false, then there is a transition to the next condition. If none of the conditions is not true, the branch is executed otherwise.

This cycle is good because from it we can deduce anything, then there is a common basic design.

1. An infinite loop (and otherwise optional, when omitted, they are not needed):

the

It is assumed that somewhere inside the loop will an if with the condition of completion and the exit button.

2. Cycle with a precondition:

the

3. Loop with postcondition:

the

4. Cycle with meter (will take an integer counter variable for example):

the

5. Loop with the exit in the middle:

the

6. And even the cycle Dijkstra!

Let's see what happens. An infinite loop is intuitive and concise, no extra words, so just leave it as is. Loop with postcondition is less common for and while loops, so in some designs it makes no sense. If such a loop is still needed, it can be easily deduced from the overall design, since it turned clear and concise.

But the loops with a precondition and with the counter turned out to be more clumsy. As they are often needed, it makes sense to implement as separate words:

1. Cycle with a precondition:

the

2. The cycle counter:

the

3. And the cycle with the postcondition (if so desired):

the

Note an important point: the loops and the loop can be implemented as a simple text substitution. Indeed, if the while loop is replaced by "repeat when", and end-while "otherwise exit repeat end repeat", you get a total cycle. Similarly, a cycle with a postcondition: loop on "repeat", until "" and end-loop "when not do exit repeat end repeat". The cycle repeat, if desired, can be converted into a set of if.

That is, we need to implement in the compiler, only the two loop: repeat and for. The loops and the loop can be done on text substitutions means of the language itself. A similar approach is taken in Eiffel and Lisp: we have the generalized structure (for example, the loop in Eiffel and cond in Lisp), which can be very flexible to use. New designs, if possible, implemented on top of the old. In Forte, the principle is the opposite: we have a lot of individual cases and the tools with which we, if necessary, can create the desired design.

Each approach has its pros and cons. The approach from the "General to specific" good at high level programming, because the programmer does not have to look at the "guts" of the translator and wise with implementation of another bike. In the Fort will first have to examine the inside of the Fort system and to introduce new words, but then there is a possibility to use a new word, which is performed quickly and efficiently. Not that one approach is better than another, they are just different. Because I care about readability and simplicity for beginners, I took the first approach as the primary.

Similarly dealing with conditional expressions. A generalized design (Hello, Lisp!):

the

Working cond similar to repeat, but only once, not repeatedly. For early exit, provided the exit-cond. Cond can also be deduced from the repeat: just after each when-branch to put the exit button. So!

Although using cond you can do any branching complexity, some common patterns useful to implement it separately.

1. A simple conditional statement:

the

2. But the case was specific to stack-based programming. Suppose we have some variable x and we need depending on the value of x to perform a specific cond-branch. Before every when in a cond or before each if (depending on the implementation), we will have to put dup, that is to take care of the duplication and/or drop'e extra items:

the

"Noise" words are completely superfluous. Indeed, if such situations occur regularly, why not automate dupы and dropы, increasing the readability and conciseness? But if we want to compare two variables? But if three? That's how many will have with the stack before each condition wise!

Especially for such situations need design case — more "intelligent" variant of cond. The syntax is very similar:

the

The main difference is that each time before when the compared items are doubled, and before the end-case of the stack extra copies are removed. That is, case = cond + placed dup and drop. Number-compare-items indicates how many items are on the top of the stack we need to double:

the

Well, the building blocks we already have. Remained solution — definition of new words. Such words are called through the call, speaking in terms of language of the assembler:

the

the

But such words work using text substitution: name is replaced by the body. As you might guess, while, loop, and if you can implement the macros as follows:

the

We introduce another familiar word for beauty:

the

Now you can very simply and clear to write something like

the

Total: thanks to flexible structures repeat and cond with elementary textual substitution, it is possible to implement a set of building blocks for all occasions. Unlike the Fort, it is not necessary to think about implementation, we abstradrome from implementation details.

For example, the word when in cond, and repeat is more cosmetic in nature: it allows you visually separate the condition from other words. But in fact, some role is played by the word do. Want the ultimate concise?

the

write

the

absolutely no hesitation on the implementation of the translator. That's not our concern, we are on a high level!

Next time we will talk about parsing the compiler's source code, stacks, data and variables.

Article based on information from habrahabr.ru

Let's just dot the i: I'm not trying to write a replacement for the Fort. Fort mid — level family of programming languages that continues productive to solve tasks and at peace not going. But I think in a different niche: high-level stack-based language with an emphasis on ease of reading programmes for beginners (if possible). A great tradition and vysokoprochnost has its advantages, but it lost some features (including positive) of the Fort.

The new imaginary language of their own philosophy and their concepts. This is what I will continue to write.

the Choice of loop constructs

Every Creator of language, which is not only recursion, sooner or later think about a set of circular structures. I prefer first to consider the design of a common, universal cycle, from which we can derive the rest, and then on the basis of practical experience, add additional designs for the most common cases.

The main loop looks like this:

the

repeat

any words

when condition1 do слова1

when condition2 do слова2

when the условиеN do словаN

otherwise a branch-or

end-repeat

Scary, isn't it? But really it is only a formal description, works all elementary. Each iteration executed all words after repeat. Then calculation of the when conditions. If condition1 is true, execute слова1 and the cycle starts a new iteration from the beginning. If condition1 is false, then there is a transition to the next condition. If none of the conditions is not true, the branch is executed otherwise.

This cycle is good because from it we can deduce anything, then there is a common basic design.

1. An infinite loop (and otherwise optional, when omitted, they are not needed):

the

repeat

any words

end-repeat

It is assumed that somewhere inside the loop will an if with the condition of completion and the exit button.

2. Cycle with a precondition:

the

repeat

when the condition is true? do body of the loop

otherwise exit-repeat

end-repeat

3. Loop with postcondition:

the

repeat

the body of the loop

when condition exit do exit repeat

end-repeat

4. Cycle with meter (will take an integer counter variable for example):

the

repeat

counter @ (counter test)

when 100 < do

|counter @ ++| set counter (incremented by one counter, if it is less than 100)

the body of the loop

otherwise exit-repeat

end-repeat

5. Loop with the exit in the middle:

the

repeat

some code

when are we going out? do exit-repeat

otherwise continue

some-other-code

end-repeat

6. And even the cycle Dijkstra!

Let's see what happens. An infinite loop is intuitive and concise, no extra words, so just leave it as is. Loop with postcondition is less common for and while loops, so in some designs it makes no sense. If such a loop is still needed, it can be easily deduced from the overall design, since it turned clear and concise.

But the loops with a precondition and with the counter turned out to be more clumsy. As they are often needed, it makes sense to implement as separate words:

1. Cycle with a precondition:

the

while condition do

words

end-while

2. The cycle counter:

the

for VariableName initial-value to ending-value step step do

words

end-for

3. And the cycle with the postcondition (if so desired):

the

loop

words

until a condition of release

end-loop

Note an important point: the loops and the loop can be implemented as a simple text substitution. Indeed, if the while loop is replaced by "repeat when", and end-while "otherwise exit repeat end repeat", you get a total cycle. Similarly, a cycle with a postcondition: loop on "repeat", until "" and end-loop "when not do exit repeat end repeat". The cycle repeat, if desired, can be converted into a set of if.

That is, we need to implement in the compiler, only the two loop: repeat and for. The loops and the loop can be done on text substitutions means of the language itself. A similar approach is taken in Eiffel and Lisp: we have the generalized structure (for example, the loop in Eiffel and cond in Lisp), which can be very flexible to use. New designs, if possible, implemented on top of the old. In Forte, the principle is the opposite: we have a lot of individual cases and the tools with which we, if necessary, can create the desired design.

Each approach has its pros and cons. The approach from the "General to specific" good at high level programming, because the programmer does not have to look at the "guts" of the translator and wise with implementation of another bike. In the Fort will first have to examine the inside of the Fort system and to introduce new words, but then there is a possibility to use a new word, which is performed quickly and efficiently. Not that one approach is better than another, they are just different. Because I care about readability and simplicity for beginners, I took the first approach as the primary.

conditionals

Similarly dealing with conditional expressions. A generalized design (Hello, Lisp!):

the

cond

when condition1 do ветвь1

when condition2 do ветвь2

when the условиеN do ветвьN

otherwise a branch-or

end-cond

Working cond similar to repeat, but only once, not repeatedly. For early exit, provided the exit-cond. Cond can also be deduced from the repeat: just after each when-branch to put the exit button. So!

Although using cond you can do any branching complexity, some common patterns useful to implement it separately.

1. A simple conditional statement:

the

if condition

ветвь1

else

ветвь2 (of course, optional)

end-if

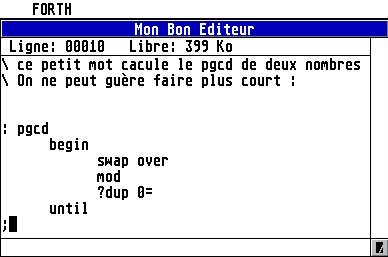

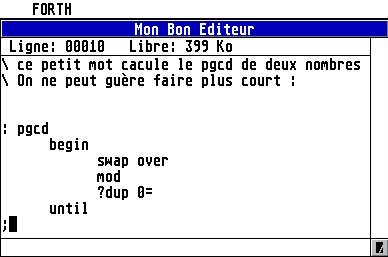

2. But the case was specific to stack-based programming. Suppose we have some variable x and we need depending on the value of x to perform a specific cond-branch. Before every when in a cond or before each if (depending on the implementation), we will have to put dup, that is to take care of the duplication and/or drop'e extra items:

the

: testif

dup 1 = if ." One" else

dup 2 = if ." Two" else

dup 3 = if ." Three"

then then then drop ;

"Noise" words are completely superfluous. Indeed, if such situations occur regularly, why not automate dupы and dropы, increasing the readability and conciseness? But if we want to compare two variables? But if three? That's how many will have with the stack before each condition wise!

Especially for such situations need design case — more "intelligent" variant of cond. The syntax is very similar:

the

case number-compare-elements

when condition1 do ветвь1

when condition2 do ветвь2

when the условиеN do ветвьN

otherwise a branch-or

end-cond

The main difference is that each time before when the compared items are doubled, and before the end-case of the stack extra copies are removed. That is, case = cond + placed dup and drop. Number-compare-items indicates how many items are on the top of the stack we need to double:

the

x @

y @

case 2 [x y -- x y x y]

when = do "equal to" print-string

when < do "y more" print-string

otherwise the "x more" print-string

end-case

Enter new words and describe the substitution

Well, the building blocks we already have. Remained solution — definition of new words. Such words are called through the call, speaking in terms of language of the assembler:

the

define name body end

the

define-macro name body end-macro

But such words work using text substitution: name is replaced by the body. As you might guess, while, loop, and if you can implement the macros as follows:

the

define-macro while

repeat when

end-macro

define-macro end-while

otherwise exit-repeat

end-repeat

end-macro

define-macro loop

repeat

end-macro

define-macro until

end-macro

define-macro end-loop

do not exit repeat

end-repeat

end-macro

define-macro if

cond when do

end-macro

define-macro else

otherwise

end-macro

define-macro end-if

end-cond

end-macro

We introduce another familiar word for beauty:

the

define-macro break!

do exit-repeat

end-macro

Now you can very simply and clear to write something like

the

repeat

...

when 666 = break!

...

end-repeat

Total: thanks to flexible structures repeat and cond with elementary textual substitution, it is possible to implement a set of building blocks for all occasions. Unlike the Fort, it is not necessary to think about implementation, we abstradrome from implementation details.

For example, the word when in cond, and repeat is more cosmetic in nature: it allows you visually separate the condition from other words. But in fact, some role is played by the word do. Want the ultimate concise?

the

define-macro ==>

when do

end-macro

write

the

cond

x @ y @ = ==> "equal"

x @ y @ < ==> "y more"

otherwise the "x more"

end-cond

print-string

absolutely no hesitation on the implementation of the translator. That's not our concern, we are on a high level!

Next time we will talk about parsing the compiler's source code, stacks, data and variables.

Комментарии

Отправить комментарий